The hashtag MaybeHeDoesn’tHitYou was started by Afro-Latina artist and writer Zahira Kelly to raise awareness of abuse that isn’t physical or visible. From there, hundreds of women shared their stories of abuse online.

This hashtag became a powerful means to highlight accounts of verbal abuse, control, and manipulation—revealing that there doesn’t have to be physical violence for a relationship to be abusive.

Even though this hashtag is now a couple weeks old and time moves fast on the internet, I wanted to bring this up today. I went to a local bookshop last night to look for summer reads and as I approached the cashier to buy a book, I overheard her talking to her coworker.

“People don’t notice emotional abuse,” she said. The woman she was speaking to nodded. “They don’t notice the difference between a bad relationship and a normal one.”

The rest of the conversation was a little hazy because I was listening from afar and not actually invited into the conversation.

But I remember she said this: “A scary number of them resonated with me.”

Then she said: “It reminded me of some of the things my boyfriend used to do.”

If this hashtag reveals anything, it reveals the scary reality of emotional abuse and manipulation and how common it is. It also reveals how difficult it is to recognize given the very narrow healthy vs. unhealthy relationship narratives we’re given.

We need to move beyond the “well, there isn’t physical violence” narrative as a means to recognize a harmful relationship. We need to move beyond ideas like “boys will be boys,” and “that’s just how things are.” The hashtag challenges this normalization and opens our minds to the fact that other forms of abuse—emotional manipulation, humiliation, control of who you can see and what you can do—to name a few.

That’s why we need to have these conversations. I think this is where the internet and social media come in as an ideal platform to start a dialogue on this.

Like the woman I overheard in the bookstore, this hashtag struck a chord with many people, including myself. In the moment, it can sometimes be difficult to label and recognize your experience for what it is. Especially given that our relationships take place within a context and a culture that downplays and normalizes bad relationships and problematic behaviors.

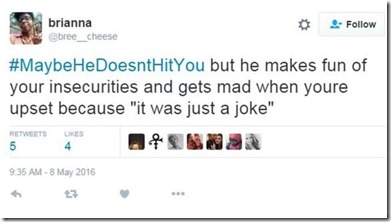

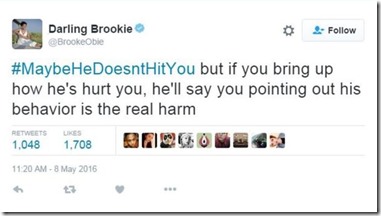

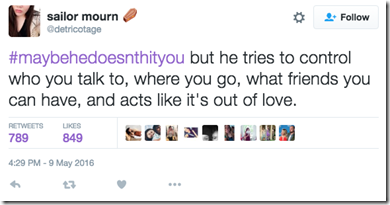

Here are a few examples of abuse women wrote about using the hashtag:

More stories can be found here.

That’s why this is important. These are real stories and experiences and we need to make sure we listen to them and know that this is not okay.

Need support? Call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-SAFE (7233).